Ever wonder how forensic analysts and information security and incident response practitioners can recreate timelines demonstrating who ran which applications and when on a Microsoft Windows machine even without fancy/expensive endpoint detection and response tools? The short answer is a lot of deep digging into features that Microsoft never intended to be used as Windows forensics tools.

In this post, I’ll explain many of the artifacts that can be found on Microsoft Windows systems, what their original purpose is (if known), and how to extract meaningful forensic data out of them.

We’re going to stick primarily to evidence of executables being run or paths where those executables can be found. Memory forensics will be out of scope for this post.

Link Files

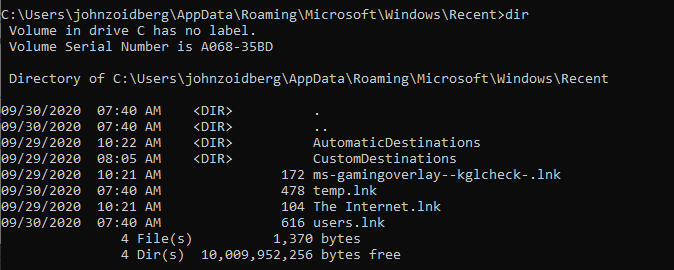

Windows uses the folder C:\Users\%USERNAME%\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Recent to store LNK files associated with files a user has recently accessed, typically by double-clicking on it in a Windows Explorer window.

If the file is reopened, it will be overwritten with the latest file access regardless of whether the file exists in a different directory.

In Windows 10 and later, Microsoft started adding the extension of the LNK file and preventing supersecretfile.xlsx from overwriting the LNK file for supersecretfile.txt.

Even so, it’s good to keep in mind that only the latest open is recorded for a given file name. It is also important to note that LNK files persist in the Recent directory, despite the file itself having been deleted. When viewing the directory in Windows Explorer the .lnk extension is never shown, even when “show file extensions” is selected in the folder options (Figure 1). These files can however be viewed via the command line (Figure 2).

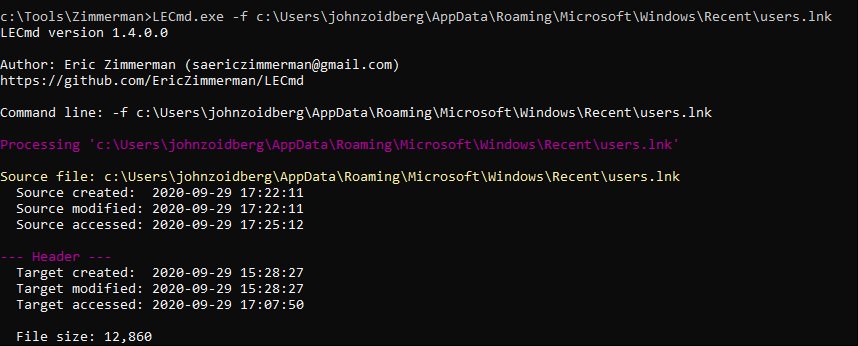

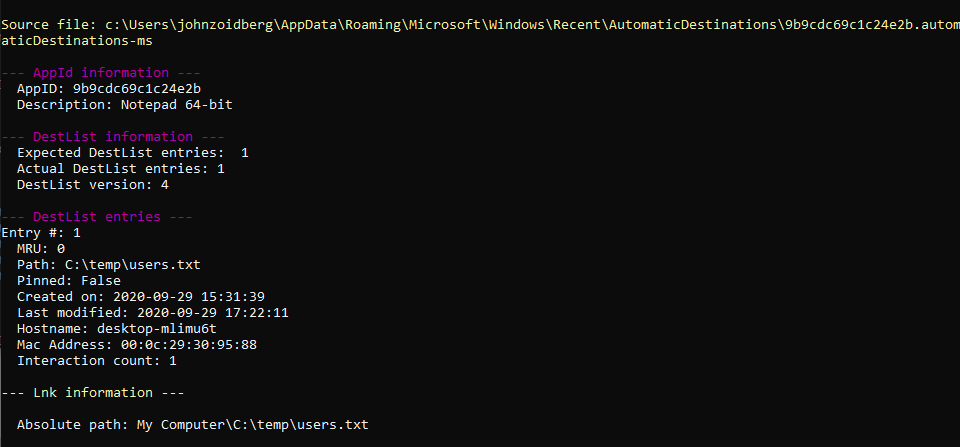

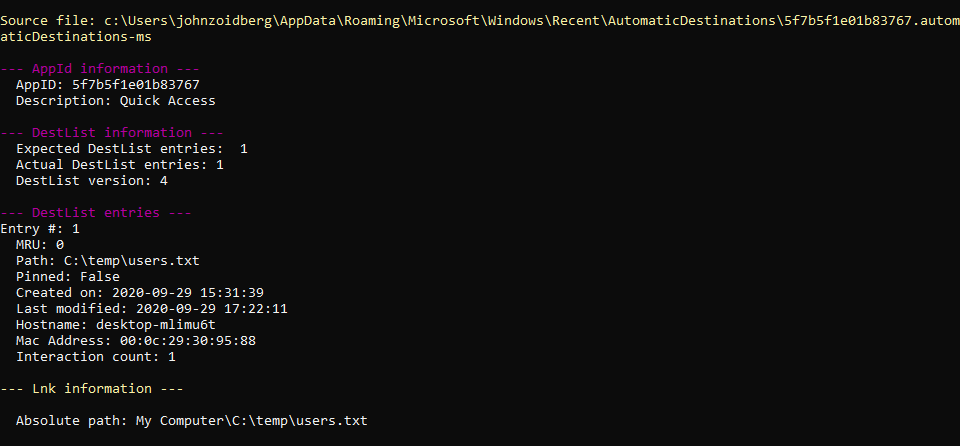

While useful, this doesn’t tell us where these files and folders actually live on disk. For that, you will need a tool like LECmd (https://ericzimmerman.github.io/). In this case, let’s take a look at that users.lnk file.

Here we can see the file’s absolute path is C:\temp\users.txt.

Jump Lists

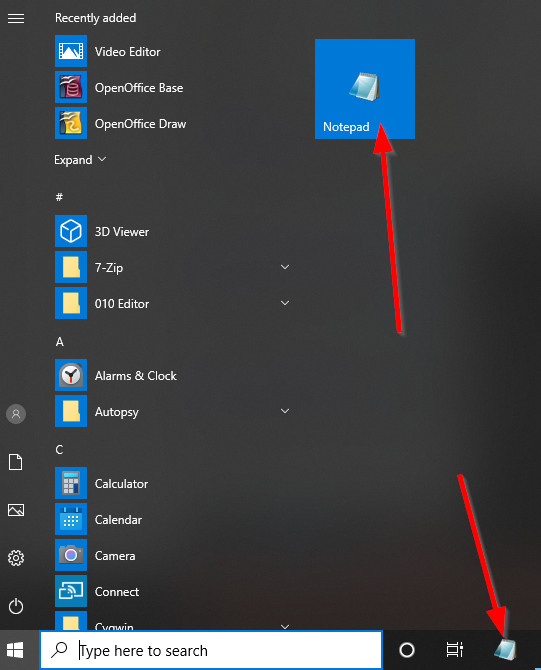

Jump Lists are files that are generated on a per-user basis for two purposes. AutomaticDestinations are auto-populated when an application associated with a file is run and stored in a subfolder within the Recent folder.

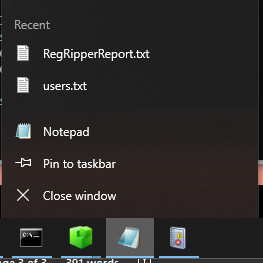

CustomDestinations folders are similarly stored in the Recent folder but are created when a user “pins” a file to the Start Menu or Task Bar.

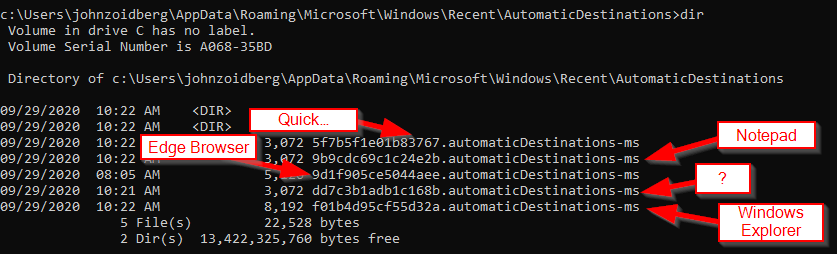

Both can be handy for demonstrating user knowledge of and interaction with a specific file or application. When viewing either of these folders, the files associated with each application are designated with a postfix of “-ms” and an AppID. The AppID requires a bit of web searching to tease out its meaning, but there are quite a few sites that have compiled large lists of them.

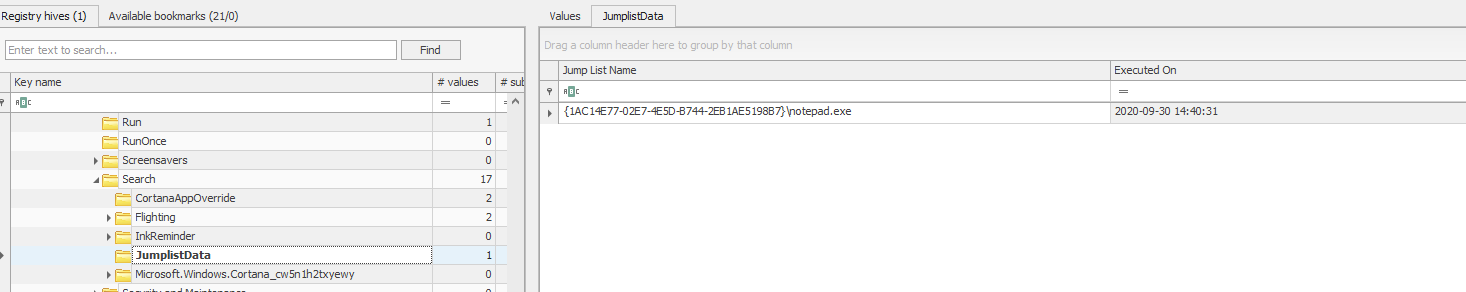

Jump Lists files themselves contain valuable information, including the last time the associated application was run and what files/LNKs were opened. To parse these, use an application like JLECmd by Eric Zimmerman (https://ericzimmerman.github.io/).

Prefetch and Superfetch

To improve application loading speed, Windows introduced Prefetch in Windows XP. Prefetch essentially grabs all of the files associated with an application from disk and writes them to memory so the user doesn’t have to wait for them to be loaded from disk.

In Vista, Superfetch was introduced which takes the concept further by tracking user behavior and attempting to predict which applications will be run and preemptively load them into memory. The Prefetch folder (C:\Windows\Prefetch) that allows these actions to take place contains files where each application is tracked in a correspondingly named.PF file and a hash of the executable.

As Windows versions mature, the available data within the .PF files have changed, but in modern Windows systems, each file contains a path to the executable, the most recent and previous seven times the executable was run, and files/directories used by the executable.

It should also be noted that Prefetch is not always enabled, particularly when the system is running on SSDs rather than spinning disk. This can be checked by examining the HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Session Manager\Memory Management\PrefetchParameters registry key. If subkeys EnablePrefetcher and EnableSuperfetch show a value of 0, the function is not enabled.

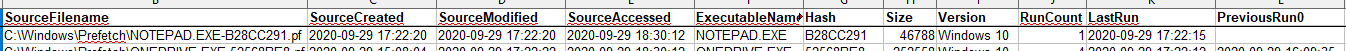

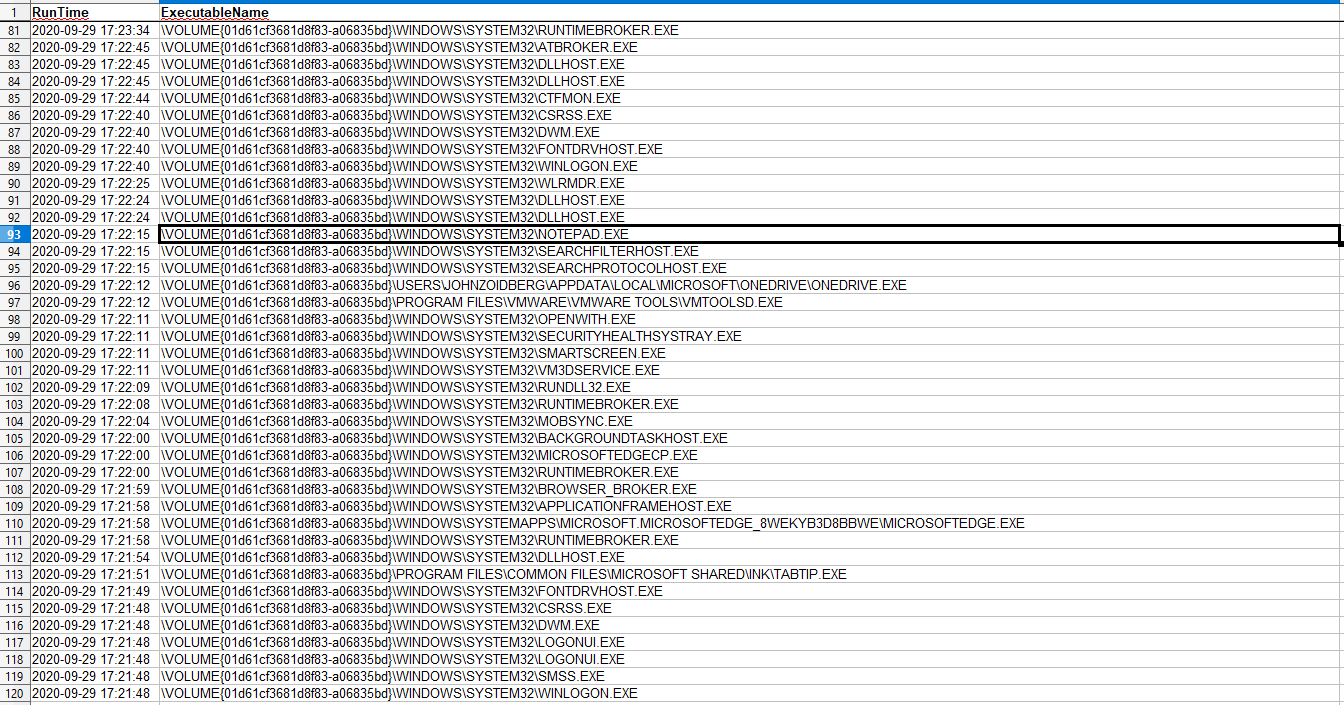

PECmd by Eric Zimmerman (https://ericzimmerman.github.io/) can be used to parse .PF files. Two files are outputted from this application. One file is a CSV containing details about each file.

As you can see by the empty space under the “PreviousRun0” field in Figure 9, Notepad.exe has only been run once. The other is a timeline generated by extracting each identified runtime with its associated executable as seen in Figure 10.

System Resource Usage Monitor (SRUM)

Ever use Task Manager to see what applications are running?

Task Manager is just a small subset of data stored in the System Resource Monitor(SRUM) database, introduced in Windows 8 for tracking resource use. The full database is located at C:\Windows\system32\sru\SRUDB.dat.

While running, Windows temporarily stores this data in the HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrenVersion\SRUM\Extensions and writes to SRUDB.dat at shutdown. SRUM contains a wealth of information about user activity including the full path to executables, CPU time in the foreground and background, and the SID responsible for execution.

You can expect to find the last 30 days of application data in SRUM.

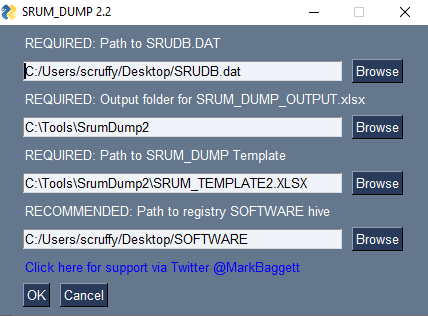

SRUM Dump 2 by Mark Baggett (https://github.com/MarkBaggett/srum-dump) can be used to examine SRUM.

SRUM Dump 2 can be used on both a live system and files from a disk image. If no arguments are passed at the command line, SRUM Dump 2 will present the user with a GUI allowing for navigation to the necessary files (Figure 11 – SRUM DUMP 2 Graphical User InterfaceFigure 11 – SRUM DUMP 2 Graphical User Interface. If attempting to grab the live SRUDB.dat or SOFTWARE registry hive, SRUM Dump2 will prompt you to download fget to generate a copy of both files.

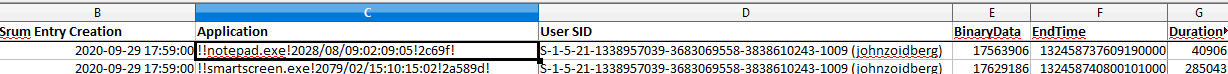

SRUM DUMP 2 outputs SRUM_DUMP_OUTPUT.xlsx which contains the executables, SID that ran the executable, date/times, network usage, and tons of other resource-related information.

Admittedly, when I ran this tool, there were parsing errors that appeared to be a misinterpretation of a field as a date. While this threw off the supposed date/time and added unnecessary garbage-looking data in the Application field, the EndTime field was accurate. This simply required converting from OLE to a more human-readable date/time format.

Registry Hives

The Windows Registry is a collection of hierarchical databases that contains information, settings, options, and other values leveraged by the Windows operating system and applications that make use of it. There’s a ton of information to help provide evidence of execution if one knows where to look for it.

- HKCU\<User SID>\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\

- Explorer\

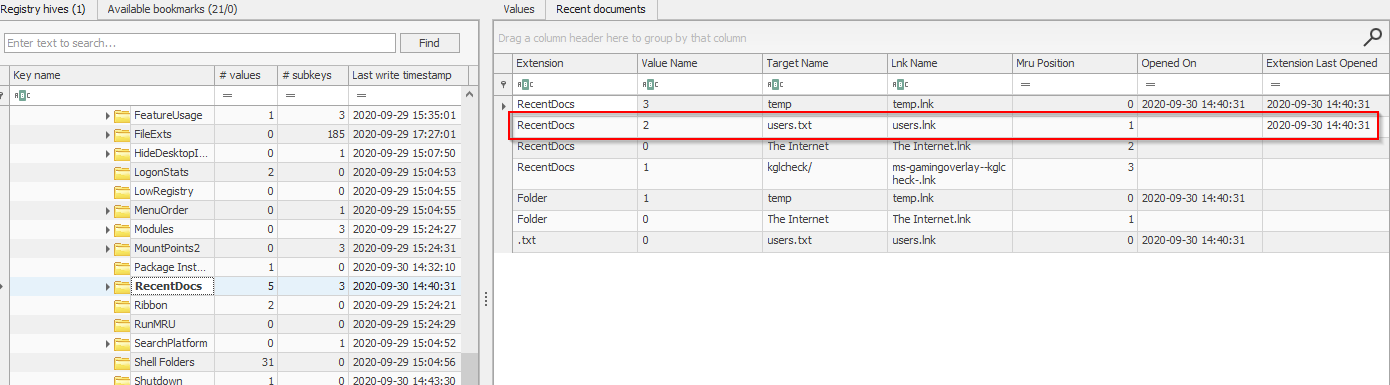

- RecentDocs – Stores several keys that can be used to determine what files were accessed by an account. The MRUListEx key shows the order in which files were accessed.

- Explorer\

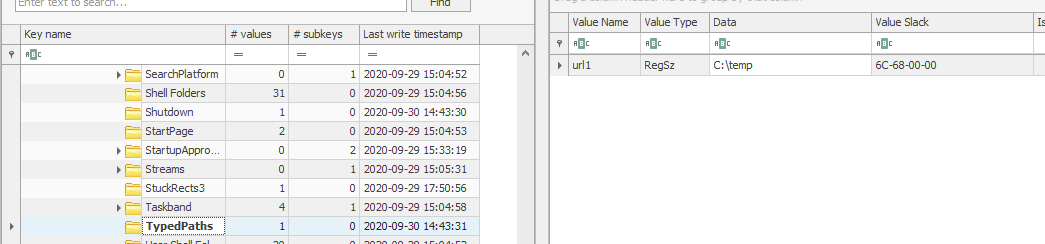

- TypedPaths – Shows items typed into the Windows Explorer bar by the user.

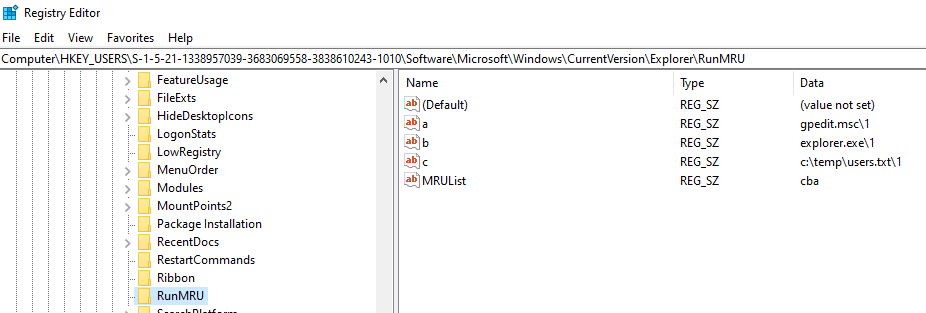

- RunMRU – Records items typed into the Windows Run dialog by the user.

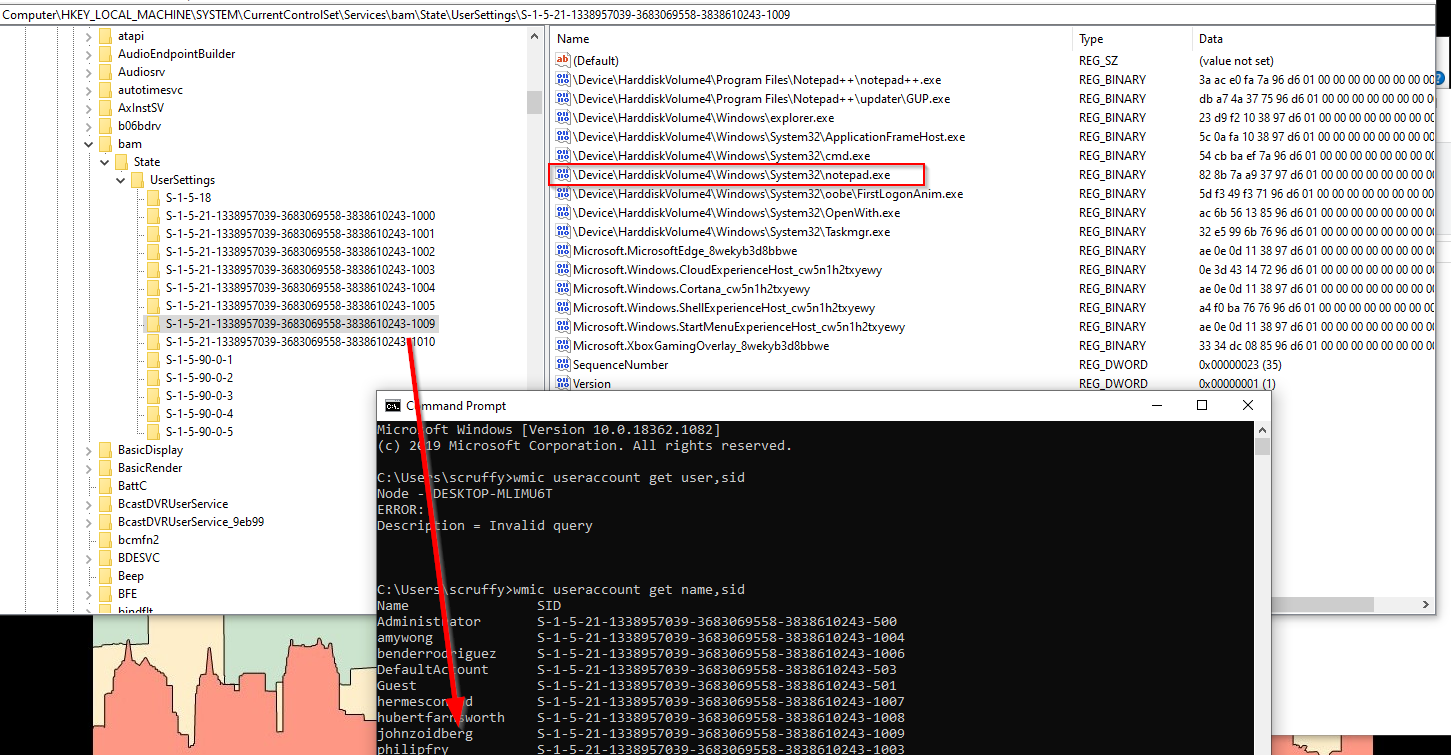

(Yes, that’s Scruffy’s SID, not Zoidberg’s. Educational purposes and all that…)

- UserAssist – ROT-13 encoded names of GUI programs that have been run and the number of times each has run.

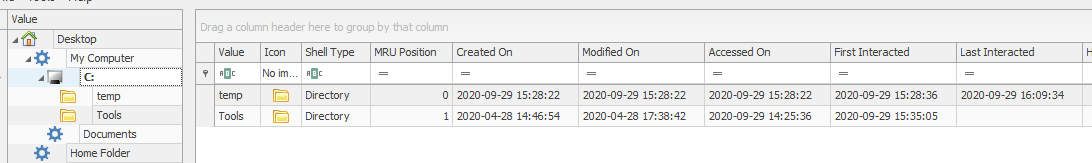

- HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\Shell – Often referred to as Shellbags, this registry location (NTUSER.DAT) and the following one (UsrClass.dat) record whenever a user accesses a folder or zip file. They can be manually parsed, but using a tool like ShellBags Explorer by Eric Zimmerman (https://ericzimmerman.github.io/) can automate much of the work.

- HKCU\SOFTWARE\Classes – Stored at C:\Users\<Username>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Windows\UsrClass.dat. This Registry Hive was added in Windows 7 to segment a section of the Registry for lower permission processes that can’t (and shouldn’t) write to more restrictive hives.

ShellBags explorer will combine both the necessary NTUSER.DAT and UsrClass.dat fields and can export a CSV or open a GUI for determining which folders a user browsed to and the corresponding interactions that user had with those folders.

- HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\

- Run\ – This location is used to execute programs at user logon and is a favorite for attackers who are looking to retain persistence on a system. In the example below, Zoidberg’s profile executes OneDrive.exe upon login, every time he logs in.

- RunOnce\ – Similar to “Run”, RunOnce is used to execute an application on the next login and is purged afterward. Also a favorite of bad actors to retain persistence, but also used legitimately for things like software installations or updates that require clean up processes after forcing a reboot.

- dam\UserSettings – dam is the Desktop Activity Monitor) and stores similar information to bam.

- HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\SRUM\Extensions – See the section on System Resource Usage Monitor (SRUM)for details.

Conclusion

As you can see, Windows has a lot of behind the scenes tracking going on to improve the user’s experience which can be leveraged by experienced forensic investigators and incident responders. It should also be noted that there is almost always one or more of these that are simply missing due to a unique configuration setting or because Microsoft modified default settings in newer versions of Windows.

If you are trying to go it alone, I hope this helps. We will plan on adding additional artifacts to look for in a future post.

Additional Resources

- Applied Incident Response by Steve Anson, ISBN: 9781119560265

- 13Cubed Introduction to Windows Forensics

If you’re looking for help in an investigation or would like to retain services for a future investigation, don’t hesitate to reach out to FRSecure.